With Republicans taking back the White House, Senate, and House of Representatives, much talk has focused on the party’s deregulation priorities. However, one of the largest and most restrictive state-based regulatory schemes has been left out of the conversation: certificate of need (CON) laws. While many states have recently made changes to their CON programs, ranging from full repeal to smaller reductions in what the program regulates, there has been discussion in the media and in the courts as to the future of CON programs. This Health Capital Topics article discusses the history of CON laws, the current landscape, and what the future may hold for CON.

The History of CON

At its core, a state CON program is one in which a government determines where, when, and how major capital expenditures (e.g., funds spent on public healthcare facilities, services, and key equipment) will be made.1 The theory behind CON regulations is that, in an unregulated market, healthcare providers will provide the latest costly technology and equipment, regardless of duplication or need, resulting in increased costs for consumers.2 For example, hospitals may raise prices to pay for underused services, equipment, or empty beds.3 Proponents of this system argue that CON programs are necessary to limit healthcare spending because healthcare consumers are unable to “shop” for goods and services, as most of these are ordered by physicians.4 Opponents of the system assert that restricting new entrants to the market may reduce competition, and create a “burdensome approval process for establishing new facilities and services,” ultimately resulting in higher healthcare prices.5 Ideally though, CON programs would not prevent change in the healthcare market but merely provide a way for the public and stakeholders to give input and allow for an evaluation process. This regulatory scheme may serve to distribute care to disadvantaged or underserved populations and block the entry of low-volume facilities, which may provide a lower quality of care.6 Wide variations among different state CON programs, however, mean that the criteria required to prove need are inconsistent.7

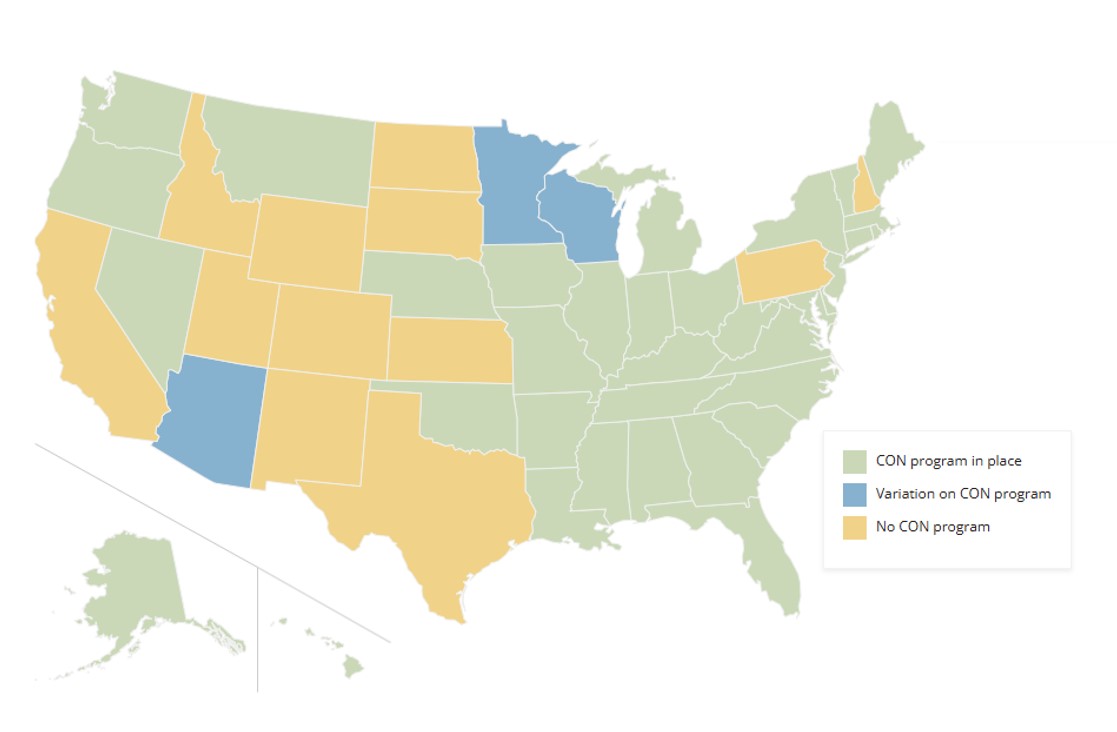

The first CON law was established in New York in 1964.8 Twenty-six states subsequently enacted similar laws over the next ten years.9 Typically, these early programs regulated expenditures greater than $100,000, as well as bed capacity expansion, expansion of services, and the establishment of new services and facilities.10 The National Health Planning and Resources Development Act of 1974 required that federal agencies pass health policy planning guidelines and establish “a statement of national health planning goals;” it also guaranteed federal funding for state CON review programs that met certain federal guidelines, causing all states to enact CON programs by 1982.11 The Act was repealed five years later, and many states subsequently repealed or modified their CON laws.12 However, 35 states still retain some sort of CON program, as illustrated below in Exhibit 1.

CON Landscape

Current CON regulation varies widely among states, with regulations based on various state statutes, rules, and regulations that designate an agency or board for reviewing and approving applications.14 The majority of states’ CON programs cover general hospitals, with some also addressing long-term care facilities and rural facilities.15 Activities that commonly require a CON review include:

The establishment of a new healthcare facility;

A change in bed capacity;

Capital expenditure greater than a state’s minimum cost threshold; and,

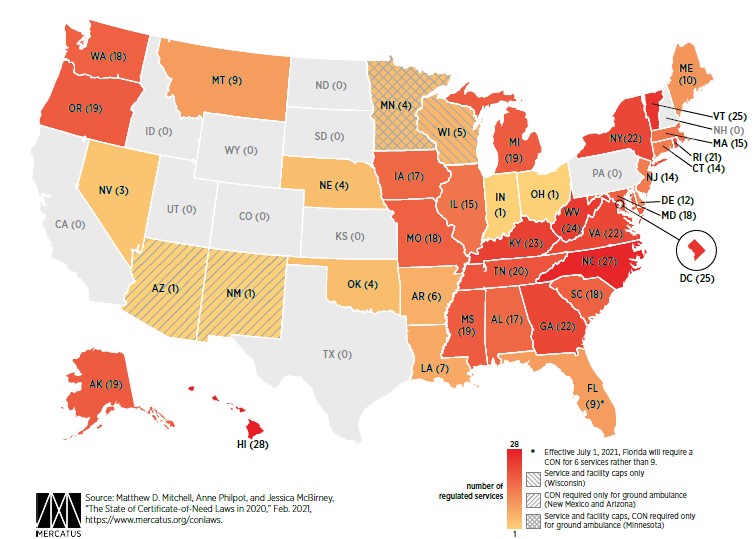

The number of services regulated by CON laws (or similar requirements) by state are set forth below in Exhibit 2.

CON application processes vary by state as well. In 20 states, applications are reviewed by the Department of Health or other state agency, while 15 states utilize an independent board or council appointed by the state government.18 The typical application process involves submission of an application for review, followed by agency review for consistency with planning criteria, and a public hearing and issuance of a decision by the granting authority.19 During a CON review, information such as how well the proposal demonstrates and fills a community need, alternatives to the proposed project, long-term project viability, the applicant’s experience in providing their proposed services, and considerations for populations of interest, including elderly or low-income residents, may be considered.20 Each state has their own unique criteria and thresholds related to the type of CON “review” that is required, e.g., Non-Substantive (no full review required), Substantive (full reviews on an individual basis), and Comparative (two or more applicants compete for projects where need is limited).21 The grant or denial of a CON application frequently results in complex and costly litigation (starting first by exhausting a party’s administrative remedies, then through appeal to the appropriate state court).

Present and Future CON Reform

Recent CON reform has focused on deregulating ambulatory surgical center (ASC) transactions. In Georgia, the state legislature has exempted single-specialty ASCs from the CON process if the entity is owned by a single physician or group and does not exceed certain operating room and capital expenditure thresholds. In North Carolina, parties seeking to establish an ASC in a county with more than 125,000 residents will not have to undergo the CON process starting November 21, 2025, although they will have to satisfy certain charity care requirements.22 South Carolina fully repealed CON laws related to all ASCs, although they still must satisfy charity care requirements.23 Tennessee similarly repealed CON laws for ASCs, although that repeal is not effective until December 1, 2027; post-repeal, ASCs that are not hospital-based will be required to participate in Medicaid and provide a certain amount of Medicaid and charity care.24 In many other states, legislators have tried repeatedly to repeal part or all of a given CON law, often to no avail, reportedly due to strong lobbying efforts by industry groups in support of the laws.25

Recent court cases challenging CON laws may potentially lead to broader reform. A case in Mississippi is challenging the state’s moratorium on new home health agencies, as a new agency has not been established in over 40 years despite growing need for home health services.26 Another, particularly important CON case worth following in North Carolina (arguably the most restrictive CON program in the country) may result in a full repeal of the state’s CON laws. In this case, a vision center wanted to begin performing eye surgeries, but was unable to do so because the state agency projected there was no need for the services in the county.27 This meant that the only way the eye surgeon could perform procedures such as cataract surgeries was at a hospital, which cost patients over $4,200 more due to the facility fee associated with a hospital-based procedure.28 The physician filed suit in 2020 challenging the CON law’s constitutionality, arguing that although the law’s goal is to keep healthcare costs down, it actually serves only to “protect[] established providers from competition.”29 In October 2024, the case reached the North Carolina Supreme Court, which vacated lower court rulings against the ophthalmologist and ordered the court to address whether the CON law violates the North Carolina Constitution.30 If in fact the law is ultimately overturned, its effects are projected to ripple across the country, and potentially impact other CON states.31

Health Capital Consultants (HCC) has assisted various healthcare organizations with drafting and submitting, as well as contesting, CON applications in numerous states. Visit us online or contact us to learn more about our services and discuss how we may be able to help.

“Certificate of Need State Laws” National Conference of State Legislatures, February 26, 2024, https://www.ncsl.org/health/certificate-of-need-state-laws (Accessed 1/22/25).

Ibid; “Why Do Some States Still Require Certificates of Need?” By Maggy Bobek Tieché, Definitive Healthcare, April 2, 2023, https://www.definitivehc.com/blog/why-do-some-states-still-require-certificates-of-need (Accessed 1/22/25).

National Conference of State Legislatures, February 26, 2024.

Pub. L. 93-641, §§ 1525-1529, 88 Stat. 2225, 2244-46 and 2249-50 (1975), 42 USC § 300k-1, 300m-4, 300m-5.

National Conference of State Legislatures, February 26, 2024.

“50-State Scan Shows Diversity of State Certificate-of-Need Laws” By Johanna Butler, Adney Rakotoniaina and Deborah Fournier, National Academy for State Health Policy, May 22, 2020, https://www.nashp.org/50-state-scan-shows-diversity-of-state-certificate-of-need-laws/ (Accessed 1/22/25).

“CON Laws in 2020: About the Update” By Matthew D. Mitchell, et al., Mercatus Center George Mason University, February 19, 2021, https://www.mercatus.org/publication/con-laws-2020-about-update (Accessed 1/22/25).

National Academy for State Health Policy, May 22, 2020.

See, e.g., “Submit a CON Application” Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, https://www.michigan.gov/mdhhs/0,5885,7-339-71551_2945_5106-120981--,00.html (Accessed 2/23/21).

“How Certificate of Need Reform Is Impacting Ambulatory Surgery Centers and What It Means for Your Business” By LauraLee R. Lawley, Parker Poe, September 27, 2024, https://www.parkerpoe.com/news/2024/09/how-certificate-of-need-reform-is-impacting-ambulatory#:~:text=Effective%20November%2021%2C%202025%2C%20there,state%20on%20an%20annual%20basis. (Accessed 1/22/25).

“Health care start-ups are trying to open. An old law stands in their way.” By Shannon Najmabadi, The Washington Post, January 2, 2025, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2025/01/02/certificate-of-need-competition-health-care/ (Accessed 1/22/25).

Ibid; Slaughter v. Dobbs, 3:20-cv-00789 (S.D. Miss.), https://www.courtlistener.com/docket/18726726/parties/slaughter-v-dobbs/ (Accessed 1/22/25).

“NC court case on health care law may turbocharge Atrium and Novant competition” By Chase Jordan, The Herald, November 4, 2024, https://www.heraldonline.com/news/business/article294878134.html#storylink=cpy (Accessed 1/22/25).

Jay Singleton D.O. and Singleton Vision Center, PA v. North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, et al., No. 260PA22, Opinion of the Court (N.C. Sup. Ct. October 18, 2024), available at: https://appellate.nccourts.org/opinions/?c=1&pdf=44132 (Accessed 1/22/25).

“Physician lawsuit could heat up Novant, Atrium rivalry” By Francesca Mathewes, Becker’s ASC Review, November 5, 2024, https://www.beckersasc.com/asc-transactions-and-valuation-issues/physician-lawsuit-could-heat-up-novant-atrium-rivalry-8-things-to-know.html (Accessed 1/22/25).