The U.S. government is the largest payor of medical costs, through Medicare and Medicaid, and has a strong influence on reimbursement to hospitals. In 2022, Medicare and Medicaid accounted for an estimated $944.3 billion and $805.7 billion in healthcare spending, respectively.1 The prevalence of these public payors in the healthcare marketplace often results in their acting as a price setter, and being used as a benchmark for private reimbursement rates.2

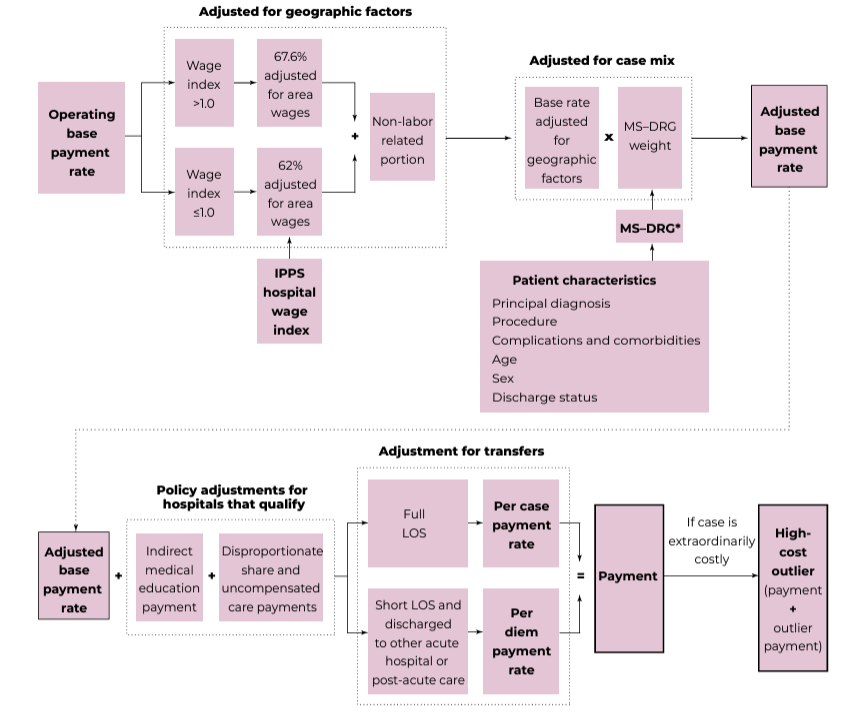

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) reimburses hospitals for inpatient stays under the Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) via two different payments: the operating payment and the capital payment.3 The operating payment covers labor and supplies costs, while the capital payment covers costs for depreciation, interest, rent, and property-related insurance and taxes.4 Further, the operating payment is split into labor-related and non-labor-related portions.5 The labor-related portion of the operating payment is multiplied by a wage index, which is calculated as the ratio of the average hourly wage of hospital workers in a given market to the national average wage for hospital workers.6 If the wage index is greater than 1.0, then the labor-related portion represents 67.6% of the operating payment; if the wage index is equal to or less than 1.0, the labor-related portion represents only 62% of the operating payment.7

Both operating and capital base payment rates have grown minimally each fiscal year for the past decade, although operating base payment rates were higher for 2020 through 2023, due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

In addition to the wage adjustment for the labor-related portion of the operating payment, the IPPS makes several other payment adjustments to account for factors specific to individual patients and hospitals. Chief among these adjustments is a modification based on the patient’s condition and the associated treatment plan, wherein Medicare assigns the patient to one of 766 Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Group (MS-DRG) classifications.8 This adjustment occurs when clinically similar conditions within the same DRG use differing amounts of resources, in which CMS may choose to reassign them to a different DRG.9 In order to calculate the operating payment, each MS-DRG is assigned a specific DRG weight, which is then multiplied by the base payment rate.10 Similarly, to calculate the capital payment, the DRG weight is multiplied by the capital base rate.11 The capital base rate is adjusted by the capital wage index and the capital cost-of-living-adjustment, if applicable, before being multiplied by the DRG weight.12

After adjusting the base payment rates for regional wage variations and the patient’s MS-DRG classification, the IPPS payment may be further modified by several factors that account for a hospital’s specific characteristics. These modifications include, but are not limited to:

Direct graduate medical education (DGME), i.e., add-on payments for hospitals that incur costs associated with training residents in approved residency programs;

Indirect medical education (IME) payments, i.e., add-on payments for hospitals that provide medical education for incurring higher patient care costs, given that they typically treat more complex patient cases;

Disproportionate share hospital (DSH) and uncompensated care payments, i.e., add-on payments for hospitals that provide services to a disproportionately large share of low income patients and patients with no insurance;

Reductions to IPPS payments due to excessive numbers of readmissions for certain procedures; and,

Outlier payments for extraordinarily costly cases.

13

The calculation of the IPPS payment methodology is illustrated in Exhibit 1, below.

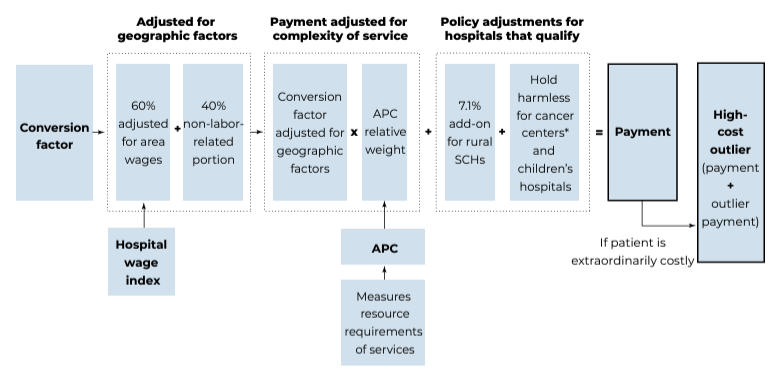

Generally, hospital outpatient costs are reimbursed under the Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS),15 under which Medicare assigns certain procedures, organized into the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS), to Ambulatory Payment Classifications (APCs) based upon their clinical and cost similarities.16 Each APC is assigned a relative weight determined by resource requirements and mean cost of the service, which is converted into a dollar amount using a conversion factor (CF).17

The CF is broken down into two components: the labor and non-labor components.18 The labor component, which comprises 60% of the CF, is multiplied by a hospital wage index to represent local economic conditions, while the non-labor component, which comprises 40% of the CF, undergoes no alterations.19 To calculate a monetary payment for outpatient services, the geographically-adjusted CF is multiplied by the APC relative weight to produce a base APC payment rate.20 In addition to this base APC payment rate, hospitals may receive additional payments under the OPPS, which include: (1) pass-through payments for certain drugs, biologicals, and devices; (2) outlier payments for extraordinarily costly cases; (3) bonus payments for certain specialized hospitals (e.g., cancer hospitals); and, (4) bonus payments for most rural hospitals.21 The calculation of OPPS payment rates is illustrated in Exhibit 2, below.

Although most hospital outpatient services are billed under the OPPS, some outpatient services billed to Medicare do not use the OPPS, even if administered in an outpatient setting.23 These services include, but are not limited to:

Certain physician services, which are designated to be paid on a physician fee schedule;

Services rendered by various non-physician practitioners (e.g., nurse practitioner, physician assistants, certified midwives, psychologists);

Services rendered by an anesthetist or a clinical social worker;

Physical therapy, occupational therapy, or speech language pathology services;

Ambulance services;

Certain prosthetics, orthotic devices, and durable medical equipment;

Clinical laboratory tests; and,

Services that the Secretary of the Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) designates as requiring inpatient care.

24

The OPPS bundles procedures performed in outpatient hospital settings such as operating rooms and recovery rooms, as well as for anesthesia services. Bundling not only encourages efficiencies and cost reductions for the hospital, but it may also stabilize payments for procedures received.

In general, inpatient admissions tend to be more profitable than outpatient services. As such, the shift from inpatient care to outpatient care may present a significant threat to hospital revenues. However, shifts in the reimbursement environment may help to offset this risk, by providing hospitals with opportunities for increased reimbursement as a reward for improved operational performance. Examples include Medicare’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP), which rewards hospitals for eliminating unnecessary readmissions, and accountable care payment methodologies, which encourage providers to reduce the number and duration of inpatient stays.25

This inpatient-to-outpatient shift over the past decade can largely be attributed to technological advancements that have allowed a broader scope of care to be delivered in an outpatient setting. In the final installment of this five-part series, the current state of the technology environment in which hospitals operate will be discussed.

“NHE Fact Sheet” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, September 10, 2024, https://www.cms.gov/data-research/statistics-trends-and-reports/national-health-expenditure-data/nhe-fact-sheet (Accessed 9/25/24).

“Medicare’s Role in Determining Prices Throughout the Health Care System: Mercatus Working Paper” By Roger Feldman et al., Mercatus Center, George Mason University, October 2015, https://www.mercatus.org/research/working-papers/medicares-role-determining-prices-throughout-health-care-system (Accessed 6/13/24), p. 3-5; “Physician Panel Prescribes the Fees Paid by Medicare” By Anna Wilde Mathews and Tom McGinty, The Wall Street Journal, October 26, 2010, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748704657304575540440173772102 (Accessed 6/13/24)

“Hospital Acute Inpatient Services Payment System” Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, Payment Basics, October 2023, https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/MedPAC_Payment_Basics_23_hospital_FINAL_SEC.pdf (Accessed 9/25/24), p. 1.

“Hospital Outpatient PPS” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, November 2, 2022, https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/hospitaloutpatientpps (Accessed 6/13/24).

“Hospital Outpatient Hospital Services Payment System” Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, October 2023, https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/MedPAC_Payment_Basics_23_OPD_FINAL_SEC.pdf (Accessed 9/25/24), p. 1.

“Hospital Outpatient Hospital Services Payment System” Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, January 2016, https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/downloads/HospitalOutpaysysfctsht.pdf (Accessed 6/13/24), p. 6.

“Hospital Outpatient Hospital Services Payment System” Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, October 2023, p. 2.

“Hospital Services Excluded from Payment under the Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System” 42 C.F.R. § 419.22.

“Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP)” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, August 5, 2022, https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program (Accessed 10/15/24).